This Thanksgiving, Ryan Curley ’23 M’24 will head home to his hometown of Marshfield, Mass., and at some point after his meal, take his dog Rio on a walk in the Marshfield Hills Cemetery.

It’s a place of deep significance for Curley. After all, it was here—on a path he’d strolled with Rio countless times before—where he made a discovery that would set him on a journey through history.

While many falsely attribute Thanksgiving to the Pilgrims, Curley knows Abraham Lincoln declared the national holiday in 1863 to unite a divided country during the Civil War, an era of American history that has long fascinated him.

But, to be fair, he’s been fascinated by many pursuits—rugby, entrepreneurship, innovation, to name a few.

In 2021, he co-founded a boutique marketing firm with his friend Nik Kasprzak ’23. The following year, he led his team to victory in the MTU Innovation Challenge, a competition through Ireland’s Munster Technical University, where they won Best Technical Solution. In 2024, he earned his MBA from Endicott while serving as a graduate assistant at the Colin and Erika Angle Center for Entrepreneurship, continuing a track record of student achievement.

In July 2023, Curley was settled into a full-time job and wasn’t looking for a new project.

But while passing through his hometown cemetery, something caught his eye.

An avid Civil War enthusiast who once dressed as a Union soldier for Halloween at age 11, Curley noticed a gravestone he’d somehow previously overlooked.

The name carved into it: Lucius Carver. Beside it, another name stood out: Allyne Litchfield.

For reasons he can’t quite explain, the gravesite and those names called to him.

He snapped a picture and he and Rio went on their way.

A Google search later turned up an engraving of Carver’s portrait and early, tantalizing morsels of information that would transform Curley’s late-night internet rabbit holes into full-on mazes.

Both Carver and Litchfield had served as Union soldiers in the Civil War, part of the famed 7th Michigan Cavalry Regiment led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer.

“Veterans Day was coming up,” Curley recalled. “I was in Halle Library waiting for a tutoring appointment, and I was telling my buddy about it. I was like, ‘Why are two men from the 7th Michigan Cavalry Regiment buried here in Massachusetts?’”

Chasing a Civil War mystery

With his square jaw and full, tight-cropped beard, Curley might pass as a Union soldier in the right light—or at least play one on TV.

Curley was “obsessed” with the Civil War as a kid, in part, because, “we don’t talk about it up here.” Growing up in Massachusetts, his childhood education was filled with tales of the Pilgrims, something Curley knew about intimately in and out of the classroom.

His 16th great-grandfather was John Alden, a cooper on the Mayflower, and Curley’s grandmother was president of the Alden Kindred of America, a genealogical society preserving the Alden Historic Site in Duxbury, Mass.

“My grandma instilled a love of early American history in me,” Curley said.

But he was especially captivated by the intersection of early American history and social justice, including a History Channel segment on abolitionist John Brown that made a lasting impression: here was a devoutly religious man who saw himself as an “instrument of God,” with a life mission to end slavery in the United States.

Curley’s parents had no particular interest in the Civil War; it was a fascination wholly his own.

But that early fascination mellowed during high school when athletics entered the picture.

Then, during his senior year at Endicott, “we took a trip to South Carolina for spring break, and I saw a lot of Confederate flags along the way,” Curley said. “And it struck me—do people not know what happened? I started getting back into it.”

Curley had no idea, however, that his cemetery stroll that day would soon propel him into the farthest corners of the Civil War.

Intrigued by those two names on a single gravesite, Curley found himself embarking on an internet journey of drama and intrigue marked by dead ends and new clues. Just as one door closed, another would open, keeping his central question alive: who were Carver and Litchfield to each other, and why were they buried together?

After combing through a digitized pamphlet from the Library of Congress, Curley soon discovered that Carver and Litchfield had been brothers-in-law—Litchfield had married Carver’s sister, Susan.

By all accounts, these were Massachusetts-born men, which led to more questions: what was the Michigan connection?

More internet sleuthing led Curley to Bob Horton, a Cape Cod resident who had commented on a blog devoted to the cemeteries of southeastern Massachusetts, a site Curley had discovered during his research.

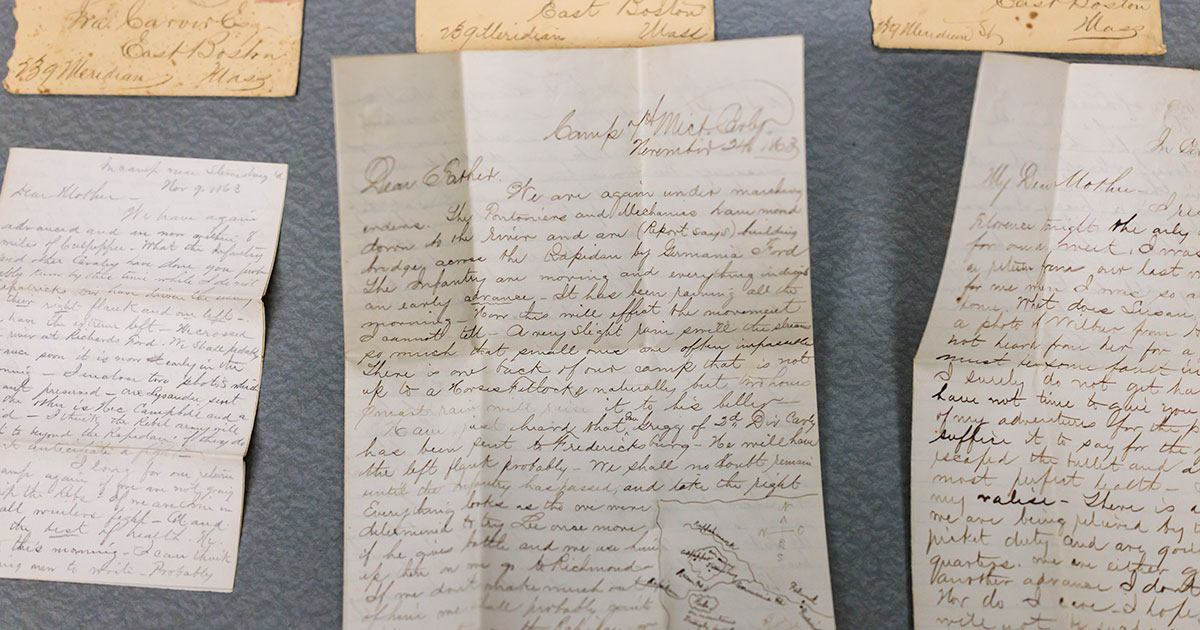

Curley had come across a 2017 blog comment from Horton mentioning a trove of letters Carver had written to his father, Ira, detailing experiences from the war.

“So, now I’m dumbfounded,” Curley said. “Not only have other people noticed this grave before, but somebody has letters from this actual soldier.”

It had been years since the original blog post, but it was worth a shot, so Curley emailed Horton and waited.

And waited.

After a month, when Curley had all but given up, phoning random Hortons on Cape Cod to track down someone who might know Bob, he was sitting in Callahan Dining Hall when he got a response.

“Bob was like, ‘Sorry it took so long, I don’t check this email anymore. I’m retired—I’m a duck boat captain now!’”

Horton, a Vietnam veteran, had obtained the letters through his son-in-law, who worked in real estate auctions, where these letters had come up for sale and attracted no interest. When Curley asked if he could see the letters, Horton delivered some disappointing news—they were being transcribed and digitized at a historical society in Western Massachusetts, meaning Curley would have to wait.

But just a few months later, that changed. The historical society lacked the resources to transcribe the delicate letters, and Horton and his wife were moving to Florida.

Horton planned to donate the letters to the University of Michigan but offered to let Curley borrow them, under one condition: Curley would have to complete the transcription and digitization work.

Not only that, but Horton insisted that the letters ultimately find their final resting place alongside Litchfield’s letters at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan.

A collaborative quest

Through his independent research, Curley had already discovered this second cache of letters from Litchfield that were housed at the University of Michigan.

In his talks with Horton, and later verified through the letters of Carver and Litchfield, Curley learned that Litchfield and Susan had relocated to Michigan. Curley theorizes that the families worked in Boston’s shipyards, where the demand for Michigan lumber played a critical role. (The Carvers are originally from Marshfield, like Curley; the Litchfields are from Hingham, Mass.)

“They’re living in Grand Rapids at the outbreak of the war. Allyne enlists and finds himself as an officer,” Curley explained.

But Carver’s correspondence to Litchfield paints a more nuanced picture.

Based on census information obtained by Curley, Carver, who was in his early 20s, was a scholar and worked as a bookkeeper living in Boston during the start of the war. As Litchfield headed southbound under Custer and the two began writing to each other, Carver became riveted by his brother-in-law’s battle tales.

Curley shared an excerpt from one of Carver’s letters: I’m at Allyne’s place but not for any time, am open for anything—I almost wish I had come out and joined Allyne’s Regiment—I’m getting a little war fever on.

“An important piece of this is that war is being mis-sold to him as an adventure, something that’s fun,” Curley said.

To understand what Litchfield was experiencing, Curley reached out to the University of Michigan in search of digital copies of his letters, only to learn that none existed.

However, a spokesperson suggested he could hire someone to photograph the originals.

His goal was to find evidence that, after Carver enlisted, Litchfield had used his connections to arrange a transfer for Carver to the 7th Michigan Cavalry Regiment, enabling the brothers-in-law to fight the Confederacy side by side.

But Curley was beginning to realize he needed more help. Simply reading Carver’s letters was arduous; it wasn’t like opening up a note from a friend today—these were meticulously crafted missives, in fine sweeping cursive, and 150 years old. In many ways, they might as well have been written in a foreign language.

Curley turned to Endicott Trustee and former EBSCO Information Services CEO Tim Collins for help. The two had been introduced by Angle Center Executive Director Gina Deschamps, and Collins, a longtime collector of artifacts from American history, was inspired by Curley’s quest.

“You’re taking a personal tour of the American Civil War, where your guides are these two brothers. It’s not like opening a textbook—you have this real human story filled with love and loss and tragedy,” Collins said. “Anytime you tell a story about American history, you can learn from it.”

For Curley, it was part history lesson, part treasure hunt—like Raiders of the Lost Ark, only this was a safe and educational adventure, one Collins was uniquely equipped to support.

Collins brought in Sydney Lagace, an independent curator with a master’s in history and museum studies from the University of New Hampshire. She’d been essential in organizing his private collection, and Collins knew she had the expertise to help Curley decode the contents of Carver’s letters.

With Collins’ financial backing, Curley also enlisted two Michigan-based freelancers: Isaac Burgdorf, a recent University of Michigan graduate, and Lenny Fritz, a junior at Hillsdale College. Burgdorf was tasked with photographing Litchfield’s letters for a digital archive and Fritz the transcription of Carver’s letters.

Connecting over Zoom and text, the group continues to collaboratively weave a vivid, human narrative of the Civil War, gradually uncovering the long-buried story of the profound conflicts that once tore America apart.

Bringing lessons of the war to a new generation

In discussions with the University of Michigan, Curley and Horton had also successfully negotiated an agreement enabling Curley’s team to lead the digitization of Carver’s letters, rather than transferring them to the university’s Clements Collection. Given the collection’s vast scope, it could take years for the letters to be processed there.

“It took a little deal-making,” Curley said.

With the support of his team and Endicott’s Halle Library—which safeguarded the letters under the College’s insurance policy, procured a waterproof and fireproof storage case, and provided a secure temporary storage space as the team prepares to ship the letters to Michigan—Curley has unraveled a more intimate and personal account of the war, as told through the voices of these soldiers.

“The letters talk about how Carver feels about major Union generals, both those that he likes and doesn't like,” said Curley. “He supports Abraham Lincoln for re-election—he says, ‘Abe's the man.’”

In handwritten cartoons, poems, and other ephemera that Carver sends, he reveals his humor, and his well-read and erudite background. In one letter he writes:

Do they think of me at home?

Do they think of me

I who shared their every grief

I who mingled in their glee

Have their hearts grown cold and strong

To the one now doomed to roam?

In the team’s research, they discover inescapable realities of war. In one letter, the team thinks they’ve spotted blood, and many letters include details about prisoner exchanges, sneak attacks by rebels, and endless death.

The letters notably provide insight into the courageous efforts of both free African Americans and runaway slaves who joined the fight alongside Union soldiers. “This marks the first time Black soldiers served in the U.S. Army in an official capacity,” said Curley.

“If I had discovered all this in high school, I might’ve been on a different career trajectory,” he added. “But I also think that because I had business training and entrepreneurial experience from the Angle Center, I can approach this project through a different lens.”

Curley explained that, because he’s not a historian and “just a guy who likes history,” he relies on his soft skills like creative problem-solving and acumen around writing proposals and obtaining funding to view the project as if it were a startup.

“Instead of creating the next software solution that’s going to change an industry’s landscape, we’re looking at the past in a way people don’t usually look at it and catering our findings towards a younger generation,” he said. “That’s the most exciting part to me.”

Curley’s new Substack presence will be part of that effort to gain traction among his generation. He plans to chronicle relevant updates while making the socio-political lessons of this period more accessible to others who might’ve grown up learning the surface-level history of the era.

One lesson Collins and Curley emphasize is that history offers insights into avoiding the mistakes of the past—because war should always be a last resort, especially when it pits neighbors and Americans against each other.

While movies and TV shows romanticize conflict, “oftentimes, wars aren’t necessary,” Collins said. “They could’ve found ways to handle things differently.”

For now, the destinies of Carver and Litchfield remain preserved in history—and in the letters, awaiting discovery.

Curley is determined to maintain the suspense surrounding their wartime experiences, holding back key details until the transcription and digitization are complete. With this groundwork laid, he hopes to attract a platform like Netflix to share this extraordinary story with a wider audience.

Yet Curley does offer a glimpse into the future that awaited Litchfield: Under President Ulysses S. Grant, he became an ambassador to modern-day India, and he and his wife went on to name their second son Lucius, after Carver.

“I like to think that if we do this correctly, we can help people learn some valuable lessons,” Curley reflected. “It’s what gives me energy.”